Culture and Religion

Liam Easley · June 26, 2020

Normally, when we think about the Assassins, the last thing that comes to mind is how they went about their everyday life. However, as a society that was actively practicing a new doctrine and was isolated not only by their own will but also by the mountains and gorges they lived among, they undoubtedly had their own way of life. Unfortunately, this culture has not yet been uncovered by archaeologists or historians.

Nevertheless, there are some scattered clues.

Hülegü Khan’s armies did not only conquer the Assassin strongholds that surrendered to them, but they also annihilated those that chose to fight back. Among those that attempted resistance was Alamūt, a castle whose biggest loss was its generously stocked library. Unlike Alamūt and other castles, the castle of Maymūndiz was not spared a shred of mercy. Its demolition was so intense that it is no longer in existence.

The library at Alamūt was said to be so bountiful that even Juvaynī, a Persian historian and Mongolian soldier who wrote extremely negatively toward the Nizārī Ismā’īlīs, admitted to his admiration of it. The library attracted scholars from all over, including Naṣīr al-Dīn Ṭūsī, a known mathematician and astronomer from the 13th century. While the works from this library are lost and scattered, it does shine a light on how the heretics were also great thinkers.

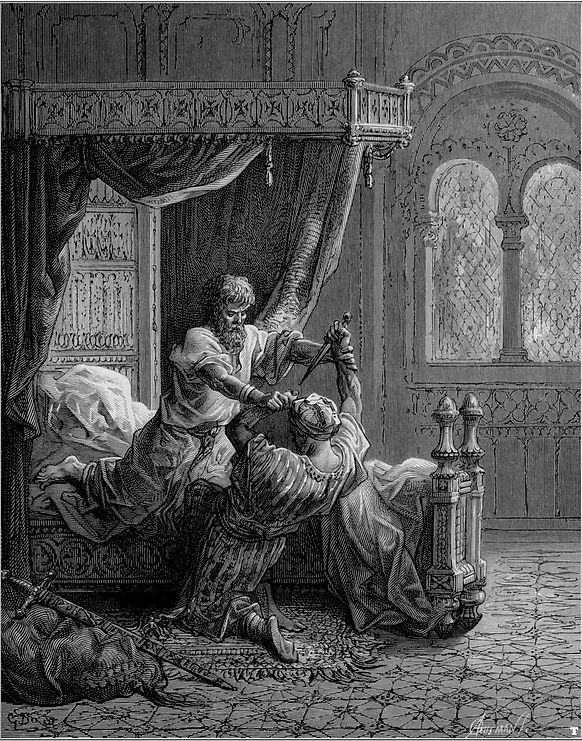

Edward I kills his assassin illustration by Gustave Doré, 1877

Additionally, it is believed that Naṣīr al-Dīn Ṭūsī built an astronomy observation deck at Alamūt. These findings were reported in 2010 by a group of archaeologists that also claimed to have found astronomy tools. Another expedition from 2018 found pieces of metal, bones and oyster shells, providing a glimpse into potential dietary preferences of the inhabitants of the castle.

From the castles that still exist in some degree, archaeologists have been able to find some remote hints to daily life such as coins, pottery, tiles and several purposeful structures like bath-houses. Of the finds, the coins offered a new dimension to the history of the sect, as some of the coins found in Alamūt had the name of ‘Alā al-Dīn Muḥammad, the Assassin leader in Persia from 1227 until his death in 1255.

The pottery shards found in Assassin castles in Persia were very similar to their contemporaries found in other communities throughout the region, meaning they all had artwork that was geometric and typically had religious implications.

What was better preserved was the religion of the Assassins, or Nizārī Ismā’īlism. The best source for Nizārī Ismā’īlī doctrine is mainly through the writings of Persian historians, since the chronicles kept by officials at Alamūt were destroyed and the resources that have survived do not provide enough to give historians an idea of what their doctrines were.

What is known is the history behind the sect.

In 1094, before al-Mustanṣir, the caliph of Cairo, died, he originally appointed his eldest son, Nizār, as his successor. However, al-Afḍal Shāhanshāh, the vizier and military commander, understood that if al-Musta’li, the younger, premature and dependent brother of Nizār, were to be caliph, he would need the guidance of the vizier in his endeavors. Thus, he had al-Musta’li marry his daughter, wrenching the caliphate from the grip of his older brother.

Nizār fled to Alexandria and led a revolt that failed under the now-corrupt state of Cairo. He was imprisoned and murdered.

When Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ took Alamūt in 1090, he and his followers likely adhered to Fāṭimid Ismā’īlism, as it was probably what he studied as a student in Cairo. However, upon this perceived betrayal, Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ became the leader of the new Nizārī Ismā’īlīs. Their headquarters became Alamūt, and the Nizārī Ismā’īlī State held a political foothold for the next 160 years. In fact, Nizārī Ismā’īlism became synonymous with the Assassins.

What is known of Nizārī Ismā’īlī doctrine is fragile, as different sources tell different stories. However, arguably the most notable religious change that came directly from Alamūt was in 1164 when Ḥasan II altered the course of the sect.

Ḥasan II, since he was a boy, busied himself with the works of Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ. He poured over them as well as Ṣūfī and other philosophic literature. What he professed helped him garner many followers in Alamūt, many of which believed him to be the imām Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ prophesied. His accession to the leadership of Alamūt was welcomed with praise.

It was on Aug. 8, 1164, the 17th day of Ramadan, when Ḥasan II spoke his new declaration. He had the nearby Nizārī Ismā’īlī populations summoned to Alamūt and ordered a pulpit to be placed in the courtyard to face west. Upon four separate pillars, flags of four colors - red, white, yellow and green - were unraveled. As the fellow Nizārīs gathered around to face the pulpit, they all faced to the east - their backs toward Mecca.

The proceedings of this event are specifically stated by many Persian and later Nizārī historians. Ḥasan II walked gracefully to the pulpit from the right, wearing a white garment and a white turban. He sat down briefly before rising again, sword in hand. He proclaimed the message given to him by a hidden imām - that the Nizārīs were chosen and relieved of the bondage of Sharī’a, or holy law. They were presented with the Resurrection, or qiyāma, and were saved from moral obligation.

Most importantly, he declared his word as divine, and that his commands be followed as if they were the words of the imām. He then welcomed his peers to break fast with him, and they did, in the middle of Ramadan. Thus began the annual Festival of the Resurrection. This ceremony was replicated at other Nizārī castles as well.

The reign of Ḥasan II was the second shortest of all the lords of Alamūt. Less than two years after his proclamation and around four years after his accession, he was slain by his brother-in-law. He was succeeded by his son, Muḥammad II, who wrote down and recorded the new teachings of his father. Being of his bloodline, he also claimed to be of divine influence. Henceforth, all Assassin leaders of Alamūt were imām.

With the accession of Jalāl al-Dīn Ḥasan III, the Nizārīs of Alamūt drew closer to Sunnism until Nizārī Ismā’īlism was reintroduced by his son, 'Alā al-Dīn.

References:

Centuries-old remnants found in Alamut castle. (2018, August 21). Tehran Times. Retrieved June 24, 2020, from https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/426728/Centuries-old-remnants-found-in-Alamut-castle

Daftary, F. (1990). The Ismā’īlīs: Their history and doctrines. Cambridge University Press.

Georgopoulos, I. (2010, November 17). Archaeologists may have located Khawja Nasir observatory at Iran’s Alamut castle. Archaeology News Network. Retrieved June 24, 2020 from https://archaeologynewsnetwork.blogspot.com/2010/10/archaeologists-may-have-located-khawja.html

Nanji, A. (2003). Nizaris. In R. C. Martin (Ed.), The Institute of Ismaili Studies. MacMillan Reference Books. https://www.iis.ac.uk/encyclopaedia-articles/nizari

Lewis, B. (1967). The Assassins: A radical sect in Islam. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Willey, P. (1963). The Castles of the Assassins. Linden Publishing.